In the last blog article, I have argued that to find out if a worldview is true or false we need to analyse how well it can explain certain facts and observations about the world. The process which evaluates rivalling explanations is called Inference to the Best Explanation[1].

Inference to the Best Explanation can be applied to various domains: for example, to evaluate competing scientific hypotheses or theories, to explain a set of historical data and -which is important for this blog articles series – to the comparison of worldviews. It can be even used when dealing with situations in everyday life. Regarding that, let’s consider the following short story:[2] I wake up after a Saturday afternoon nap. When I walk out of the house I see that both the driveway in front of the house and my car are wet. Moreover, I know that neither myself nor one of our neighbours have an automatic sprinkler. From these facts I could conclude that it rained or that somebody washed my car. With only the data of the wet driveway and the wet car I cannot conclude which hypothesis is correct. I need more data. But I know that it is very unlikely that somebody in my family including me would wash the car by hand. However, when I realize that the streets and the lawn are dry and the sky is clear, the rain hypothesis becomes nevertheless unlikely. Finally, I discover a bucket with soapy water and a sponge behind the car. With the final piece of data, the best explanation for all observations becomes obvious: someone washed the car. Let’s call this explanation 1). Alternative – but much worse – explanations are:

2) It was raining just on the driveway and someone (maybe one of my kids) left a bucket with soapy water and a sponge next to the car maybe in order to pretend that they washed it.

3) It was raining just on the driveway and someone (maybe one of my kids) actually washed the car.

Both 2) and 3) – while possible – are unnecessarily convoluted. Thus, the Inference to the Best Explanation is that somebody washed the car. It could have been my wife, one of my kids, or any of my neighbours who was not happy of the sight of a dirty car.

Note: often Inference to the Best Explanation appears together with the term abduction and abductive reasoning. While the Inference to the Best Explanation is a method of evaluating rivalling hypothesis abduction is a method of generating hypotheses.[3]

Introduction into explanatory virtues / Evaluation Criteria

To make the Inference to the Best Explanation criteria are employed to evaluate rivaling hypotheses.[4] There are various lists of criteria by different scholars[5] (which sometimes use a different name for the same criteria) and the goal of this blog post is only to give insight of in my view a couple of important criteria. In the story above the first four of the following important criteria, which are also called or explanatory virtues, come into play:

- Explanatory scope: How many of the given of phenomena, facts or observations are explained by a hypothesis, theory or in our case a worldview?

- Explanatory power: This refers to how well a hypothesis, theory or in our case a worldview explain a given set of phenomena, facts or observations.

- Plausibility: how likely does hypothesis, theory or in our case a given world view explain given data given our background knowledge, i.e. given what we already know about reality.

Note: Both plausibility and explanatory power are related. Often a plausible explanation has more explanatory power, because it already fits with existing knowledge. However, with enough evidence a less plausible explanation may win the day. - Simplicity: A simpler explanation has less assumptions/presupposition and fewer steps to provide an explanation for given facts and is therefore to be preferred.

Note: if however, for example a simpler explanation has less explanatory power for some facts then a competing more complicated hypothesis might be preferred. - Ad hoc: Closely related to simplicity is to consider if a hypothesis is ad hoc. Ad hoc means that additional assumptions are introduced to support an explanation without having additional evidence for those assumptions.

In our example above all hypotheses consider all pieces of the data and have therefore the same explanatory scope. However, the explanatory power of 2) and 3) is much smaller, because it is very unlikely that there is just rain falling on the driveway and nowhere else and in addition for 2) somebody left a bucket with soap and sponge next to the car just for fun. Thus, the car wash hypothesis has greater explanatory power. Moreover, that rain restricted to maybe 70 m2 (in combination with a clear sky) is very unlikely is well established background knowledge. Therefore, the car wash hypothesis is more plausible. It even trumps my background experience about nobody in my family would like to wash a car by hand. This example also shows the often-occurring interrelation of explanatory power and plausibility mentioned above. The car wash hypothesis is also simpler, because it needed less causes to explain the evidence. It just needs one cause: somebody washed that car. The alternative hypothesis 2) required two causes: It rained just on the driveway and for 2) somebody just left the bucket there (for no reason or pretending to wash the car etc.). Hypothesis 3) has two different causes which can result in the same effect: both rain and car wash can explain a wet car and wet driveway.

In this example I could additionally closely inspect the car and if I knew it had dirt which would not be removed by rain alone but is now not there anymore, then 1) becomes even more certain. If the car would still be dirty, then most likely the person washing the car did not a good job.

Note: Inference to the Best Explanation and abduction/abductive reasoning cannot guarantee that the explanation which has been deemed best is actual the correct one, because sometimes another alternative explanation has just not been considered. And it is not always easy to be exhaustive when generating hypothesis. The car wash example was a straightforward case.

The first two criteria (explanatory scope and power) can also be illustrated by the analogy of a jigsaw puzzle and solutions obtained for a given Puzzle:[6]

- Wrong Solution A: all parts have been used, some parts are forced in and are damaged.

- Wrong solution B: some parts missing, some parts force fitted and damaged

- Correct Solution: all parts are used and all parts fit well power

The first solution while using all parts (full explanatory scope) lacks explanatory power, because some parts are force fitted. The second solution lacks both scope and power. The third solution is preferred, because it has both explanatory scope (uses all parts) and power (all parts fit well).

Another example just for simplicity would be the explanation of an airplane crash. If the crash can be explained by 1) a simple landing system failure or by 2) combination of wing and engine failures, black smoke, and other factors then 1) would be the simpler explanation and if all other things been equal the preferred hypothesis.

Example for Ad hoc

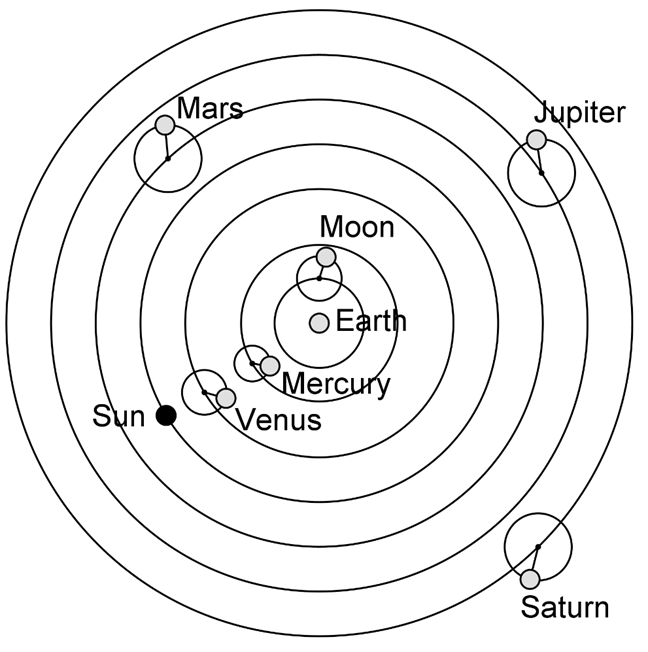

As mentioned above a hypothesis is ad hoc when additional assumptions are introduced to support an explanation without having additional evidence for those assumptions. For example, Pre-Copernican astronomy held to a geo-centric view of the universe with the Earth at its centre and the sun, moon, planets and stars revolving around the Earth. However, planetary motion could only be explained with this model by adding so called epicycles[7], for which no evidence existed. The concept of epicycles is depicted in Figure 1 below: the moon and the planets evolve not only via the big circles around the Earth but in addition around a smaller circle (an epicycle) around a centre which moves on the corresponding big circle around the Earth.

Figure 1: Geo-Centric view of our solar system with epicycles.

Nicolas Copernicus came up with a heliocentric model, i.e. sun is at the centre of the solar system and the Earth and planets moving around the sun. This model brought improvements but didn’t fully get rid of epicycles, because he still had the orbits as circles.[8] The remaining issues were resolved by Kepler’s model which introduced elliptical orbits.[9] Since the heliocentric view could explain the astronomical observations without epicycles it is the preferred to the geocentric view which required the ad hoc addition of epicycles.

Note: Sometimes new entities have to be introduced to explain new observations. For example, the concept of dark matter was introduced to explain some gravitational effects observed in stars and galaxies.[10] An alternative to dark matter is the so called modified-Newtonian dynamics. [11] Thus, in that case it is adding a new unknown form of matter versus more complicated mathematics. While most cosmologists favour the dark matter model, more data will be required to find out which theory is correct. Maybe both theories will turn out to be false and another will turn out to be correct.

Probabilistic Reasoning

In addition to the approach described above, scholars often employ probabilistic considerations when evaluating hypotheses. They employ Bayesian analysis which as summarized by philosopher of science Steven Meyer “provides a quantitative method of estimating the strength of a hypothesis or the relative probability of competing hypotheses given some body of evidence.” [12]

However, in most situations we won’t make use of this. As Meyer states “Often, our background knowledge of cause and effect (or our theoretical understanding of the causal powers of a postulated entity) will enable us to come to sound assessments of the merits of competing hypotheses without making explicit use of Bayesian probability calculus—even if our reasoning can also be explicated in Bayesian terms.”[13]

Therefore, I will not go further into details here. But if in one of the following articles we encounter an instance where a probabilistic approach would help I will consider it an provide the necessary details.

Outlook

The following blog post will give an overview of several worldviews and will outline their commonalities and differences.

[1] Peter, Liton. Inference to the Best explanation. In Martin Curd & Stathis Psillos, The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Science. (New York: Routledge,2005).

[2] This example is an adapted version of an example provided in: Stephen C. Meyer. Return of the God Hypothesis. Kindle ed. (HarperOne: 2021), 227-228.

[3] Frank Cabrera Inference to the Best Explanation – An Overview. Handbook of Abductive Cognition (Springer, ed. L. Magnani, 2022), 1-37.

[4] See for example: Cabrera, Inference to the Best Explanation – An Overview. A Brief Summary of Explanatory Virtues https://arxiv.org/html/2411.16709v1; Abductive Reasoning in Science https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/abductive-reasoning-in-science/A380186A1C38650BB9842AF9536D235D

[5] See for example the following page for different lists: A Brief Summary of Explanatory Virtues https://arxiv.org/html/2411.16709v1

[6] Example adapted form Licona, Michael. The Resurrection of Jesus: Authority & Method in Theology: A New Historiographical Approach ( InterVarsity Press, 2010), 109-110.

[7] Figure: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/Ptolemaic_Model.png

[8] Guillermo Gonzalez and Jay W. Richards. The Privileged Planet (20th Anniversary Edition): How Our Place in the Cosmos Is Designed for Discovery (Gateway Editions, 2024), 210 pp.

[9] Ibid., 214 pp.

[10] Luke A. Barnes and Geraint F. Lewis. The Cosmic Revolutionary’s Handbook: (Or: How to Beat the Big Bang).Kindle-Version. (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 2.

[11] Ibid., 230-231.

[12] Stephen C. Meyer. Return of the God Hypothesis. Kindle ed. (HarperOne: 2021), 232.

[13] Ibid., 235.

Leave a Reply